Meat & Livestock Australia| 04 October 2017

Identifying the genetic merit of your animals

With genetics, what we see is not always what we get. This is because environmental factors also have a considerable influence on most production traits. Therefore, we cannot simply say that all of the observed differences in performance between animals raised in different environments and/or different management groups is due to their genetics.

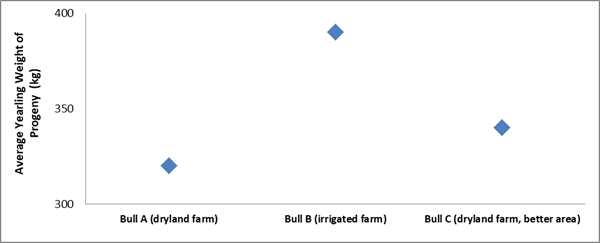

In the example illustrated in Figure 1, we are comparing three bulls used on three different properties that have differing levels of feed availability. Based purely on the raw average yearling weights of each bull’s progeny, it is impossible to know whether Bull B has superior genetics or whether his progeny’s heavier weights are a function of the environment in which they were raised (on irrigated pasture). Nutrition is just one of the many environmental factors that can influence production traits. It is important to note that these factors can occur not only between properties, but between mobs and even within a single mob on a property. Two classic within mob examples are the presence of twins or individuals being sick or injured in an otherwise healthy herd.

Figure 1: The average progeny yearling weight of Bull A, Bull B and Bull C, where the progeny were bred and raised on different properties.

The BREEDPLAN analysis removes the environmental factors from each animal’s raw performance and calculates EBVs. To achieve this, BREEDPLAN uses three sources of information; these are pedigree, trait records (from the individual itself and its recorded relatives) and, for some breeds, genomic information.

To allow BREEDPLAN to compare animals in different management groups (e.g. the scenario in Figure 1), there needs to be a genetic link between each group and/or property. A sire used in multiple groups passes on the same genetic merit regardless of the group (or environment) he is used in. Therefore, by comparing the progeny of the link sire against the progeny of Bulls A, B and C on each individual property, we can evaluate the relative genetic merit of all the bulls involved.

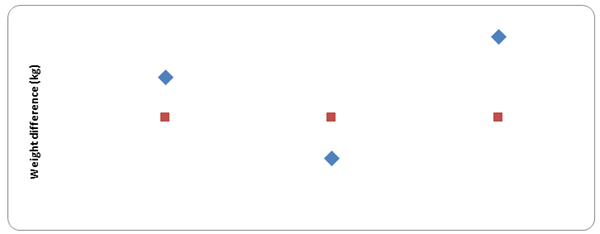

As Figure 2 shows, the progeny of Bull A were 10kg heavier on average at 400 days of age than the link sire’s progeny, while the progeny of Bull B were on average 10kg lighter at 400 days of age than the link sire’s progeny. The progeny of Bull C were on average 20kg heavier than the progeny of the link sire at 400 days of age. Given that the genetic merit of the link sire does not change (e.g. any difference in average 400 day weight of the link sire’s progeny on each property is due to environmental factors), we can deduce that Bull A and C are genetically superior to the link sire for 400 day weight, and Bull B is genetically inferior to the link sire for 400 day weight. As a result, we would expect that the 400 day weight EBVs for Bulls A, B and C will be 20kg heavier, 20kg lighter and 40kg heavier, respectively, than the 400 day weight EBV of the link sire.

Figure 2: Average adjusted progeny performance for the three different sires (blue diamonds) benchmarked against the average adjusted progeny performance of the link sire (red square).

Accuracy of your genetic merit estimates and thus the accuracy of your subsequent selections

While it is possible to generate reliable EBVs from performance that has been recorded on correlated traits, generally speaking EBVs will be of lower accuracy if animals have not been directly recorded for the trait of interest. By definition, an EBV is an estimate of an animal’s true breeding value. The higher the accuracy, the more likely the EBV will predict the animal’s true breeding value and the lower the likelihood of change in the animal’s EBV as more information is analysed for that animal, its progeny or its relatives. Ultimately, the higher the EBV accuracy, the more informed and reliable the selection decisions are that are made, and the more genetic improvement that can be achieved.

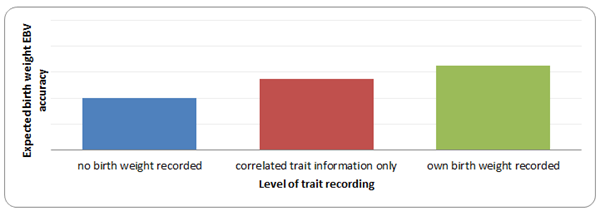

Consider these animals:

- Animal A with no trait records (no birth weight or 200 day weight).

- Animal B with a correlated trait record (200 day weight) but no record for the trait in question (birth weight).

- Animal C with a record for the trait in question (birth weight) but no correlated trait records.

Indicative EBV accuracies for Animals A, B and C are displayed in Figure 3. It is important to note that these values are indicative only, as the exact EBV accuracies for an animal will vary depending on a number of factors. These factors include:

1. the heritability of the trait

2. the EBV accuracy of the parents

3. the amount of performance information available

4. the effectiveness of the performance information (e.g. contemporary group structure)

5. genetic correlation with other measured traits. For example, we would expect that the EBV accuracies would be lower for traits (e.g. fertility) that are less heritable than birth weight. Equally, if the genetic correlation between the two traits was lower, then the difference in EBV accuracy between Animals B and C would be greater.

Figure 3: The expected birth weight EBV accuracy for three animals with differing levels of trait recording.

The take-home message from these results is that EBV accuracy is improved by:

- recording as much data as possible

- if recording a trait is not practical (e.g. expensive or difficult to measure), then recording a correlated trait is beneficial though not as effective as recording the actual trait

- using information from correlated traits is also ineffective if you are trying to select against the known relationships between traits. See the ‘curve bender’ section in part two of this article for more detail.

- to collect effective information for the BREEDPLAN analysis, breeders should aim to have a minimum contemporary group size of six animals, with at least two sires represented in each contemporary group.

BREEDPLAN can analyse up to two weights for each of 200, 400 and 600 day weights, and up to four mature cow weights per animal. Recording such repeated records can improve the accuracy of the resulting EBVs.